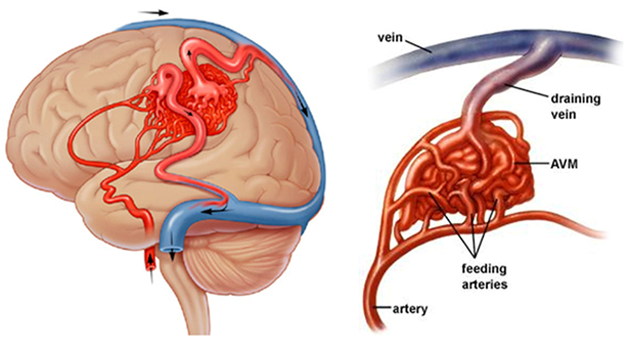

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is an abnormal tangle of blood vessels that can occur anywhere in the body. In an AVM, blood does not follow its normal path, but instead flows directly from arteries into veins, without passing through the tiny capillaries that normally separate the two. Veins, designed to accept blood from minuscule capillaries, become stressed and damaged by the higher flow rate and pressure of blood flowing in from arteries.

An AVM can give no signs at all — indeed, some people may have AVMs and never know it — but AVMs can also be life-threatening depending on their size and location, and whether they rupture and bleed. They can also lead to the development of an aneurysm in either the arteries or veins.

When it occurs in the brain, an arteriovenous malformation is known as a cerebral AVM or a brain AVM. It can occur deep in the brain (in the thalamus, basal ganglia, or brainstem), or on the brain’s surface. When an AVM occurs in the dura mater — the thick, leathery covering that surrounds the brain — it is known as a dural AVM, or duralarteriovenous fistula (AVF). A cerebral or dural AVM can cause headaches, seizures, and other symptoms, but it can also be completely silent.

An AVM may also occur in the spinal cord, where it can cause back pain, sensory loss, and weakness in the extremities. Ten to 20 percent of spinal AVMs cause a sudden onset of symptoms rather than a slow progression. In these cases an abnormal vessel may have burst, causing bleeding (ahemorrhage) and resulting in weakness, numbness, and other neurological deficits.

The greatest risk of an AVM is rupture and bleeding — a ruptured AVM (either a subarachnoid, subdural, or intraparenchymal hemorrhage) can cause a stroke or produce other temporary or permanent brain or spinal cord damage or even death.

After aneurysms, cerebral AVMs are the next leading cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Even if the AVM does not rupture, it can cause pain and damage if it grows large and creates pressure against the brain tissue surrounding it. That pressure can also lead to seizures, and can interfere with the free movement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), causing hydrocephalus. Since an AVM can interfere with the delivery of oxygen to brain tissue, it can damage otherwise healthy brain cells nearby.

Cerebral and spinal AVMs are thought to be genetic in origin, so they cannot be prevented. Dural AVMs, on the other hand, are usually not genetic — they appear to be the result of venous thrombosis (clotting of the veins), often due to trauma, infection, or surgery. They often occur when a portion of the circulatory system in the brain becomes obstructed with a thrombus (blood clot) and the body grows new blood vessels to bypass the clot. This process, known as angiogenesis, can lead to the development of a dural AVM.

Although a genetic AVM is present from birth, it may not cause any symptoms until early adulthood or middle age, after years of damage to the brain tissue. Pregnancy may cause symptoms to appear due to changes in blood flow and blood volume. After middle age, an AVM becomes stable and less likely to cause symptoms.

Men are more likely to develop AVMs than women, and those with a family history of vascular malformations are also at higher risk.

Symptoms of a spinal AVM include:

- Chronic back pain

- Sudden, severe back pain

- Progressive or sudden numbness or weakness in the legs or arms

The most frequent — and serious — signs of a brain AVM are the symptoms of an intracranial or subarachnoid hemorrhage, or bleeding in the brain, which is a neurological emergency that requires immediate care. Nearly 50 percent of patients with an AVM will have the malformation identified only after a hemorrhage. These symptoms may start with a sudden-onset headache, often described as “the worst headache in my life,” the sudden onset of seizures, and may also include: Loss of consciousness or diminished alertness, Weakness and/or numbness in part of the body, Aversion to bright light, Double vision, vision loss, or other vision changes, Confusion or irritability, Neck and shoulder pain, or a stiff neck and Nausea and vomiting.

Many patients who are diagnosed with an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) only find out about their condition in the emergency room after a rupture. Others are diagnosed when the AVM is seen on a CT scan or MRI, which may have been performed after an accident or injury or may have been ordered by a neurologist to investigate the cause of a patient’s headaches or other symptoms.

Computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are noninvasive procedures that produce images of brain or spine structures and detect bleeding. CT scans use X-rays and MRI scans use magnetic fields to create images of the brain or spine. CT and MR scans detect the AVM but are not precise enough to see the details of an AVM’s structure and location, which are best seen on a cerebral angiography (angiogram).

Cerebral angiography, also called 6 vessel DSA, is a minimally invasive procedure that provides a detailed image of blood flow in the brain. An angiogram is the gold standard for diagnosing and evaluating AVMs. To perform an angiogram, a specialist called an interventional neuroradiologist inserts a catheter (a small plastic tube) into a blood vessel and feeds it gently toward the location of the suspected AVM. A special dye called a contrast agent is injected through the catheter and makes its way to the malformation. The path of the contrast agent, when viewed on an X-ray, produces an image of the AVM’s structure and allows the neuroradiologist to locate the AVM precisely within the brain or spinal column.

The recommended treatment plan will be based not only on the angiogram but also on the patient’s clinical history, age, symptoms, and a physical examination. For example, an older patient at low risk for bleed might be advised to have the AVM monitored rather than treated.

An Interventional neuro-radiologist evaluating the diagnostic angiogram will discuss treatment options with the patient and make a recommendation based on the risk of a rupture or other complications balanced against the risks of endovascular intervention. The decision to treat a cerebral AVM depends on its location, the risk of future complications if it is left untreated, and the risk of neurological deficits that may be associated with its treatment.

There are varieties of treatment options, which may be used alone or in combination, for the treatment of AVMs. Some AVMs will require just one of these therapies and others will require a combination.

Treatments options include:

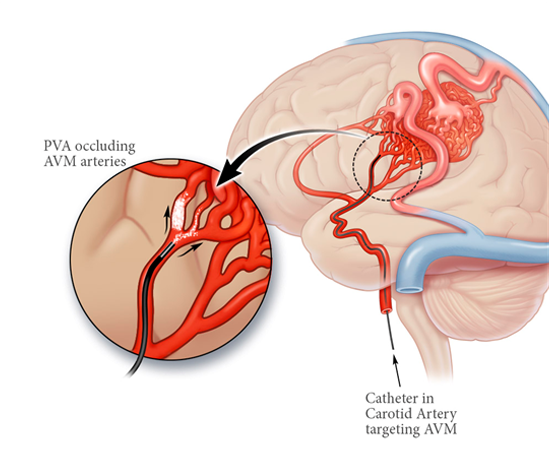

Embolization :

Endovascular approach to AVMs is endovascular embolization, which involves the insertion of a catheter, or small plastic tube, through an artery in the upper leg. The tube is guided up the circulatory system to the site of the AVM, where it delivers a liquid “glue” that embolizes (blocks) blood flow to the malformed vessels, thus restoring normal circulation. In most cases, embolization alone is not enough to cure an AVM, but is very useful to reduce the size of an AVM before surgery. In some cases it may reduce a large AVM enough to make radiosurgery a viable option, thus avoiding the need for surgical resection.

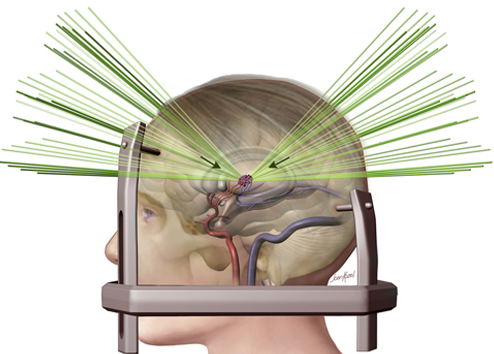

Stereotactic Radiosurgery :

Without entering the skull, neurological surgeons can use stereotactic radiosurgery (highly targeted radiation beams from multiple angles) to treat an AVM. This technique, generally used for smaller AVMs, is effective in most of the patients. Radiosurgery is usually delivered in an outpatient setting in a single treatment. The radiation, once delivered, produces a slow narrowing of the abnormal blood vessels over time.Takes one to two years to work with significant risk of bleeding during that period. It is not useful for large AVM.

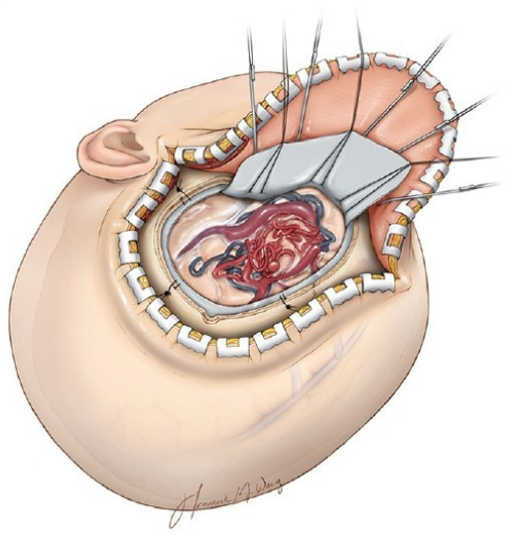

Microsurgical Resection :

Microsurgical resection of an AVM is open surgery in which the neurosurgeon removes part of the skull to gain access to the abnormal vessels, which are then repaired or removed. In cases where the risk of a hemorrhage is high, or the AVM’s location is inaccessible to an embolization catheter, this surgery may be a patient’s only option. Following this procedure, close monitoring and strict control of blood pressure are required, as well as a high-quality angiogram to determine that the AVM has been completely removed. There are risks involved in any brain surgery, including infection and neurological impairment, but a successful surgical resection that completely removes an AVM virtually eliminates the risk of a future rupture.

After surgery, radiosurgery, or embolization, your medical team will monitor your progress and conduct tests to evaluate the success of your therapy.