Nosebleeds are a very common medical problem. They generally result when the tissue that lines part of the nose erodes and certain vessels become exposed and break.

Causes include trauma, abnormalities in the structure that separates the nose into two sides (septum), irritation of the tissue lining the nasal cavity, inflammatory diseases, tumours, high blood pressure, vitamin K deficiency, hardening of arteries (arteriosclerosis) and specific blood or blood vessel disorders (such as hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia).

There are two types of nose bleeding: posterior and anterior. Anterior bleeds come from the front of the nose, and are more frequent. Posterior bleeds come from the back of the nose. These are usually heavier and more difficult to control. They are more frequently associated with complications such as airway obstruction, breathing blood into the lungs and coughing it up, and abnormally low blood plasma volume.

Most episodes of nosebleeds are self-limited, meaning the bleeding will stop without medical assistance. In rare cases, nosebleeds can be life-threatening, especially in elderly patients and those who suffer from diseases or conditions that occur together with the nosebleeds.

In most cases, blood will flow from a single nostril, but when a nosebleed is particularly heavy, it will spill into the second nostril, and may also run down the throat and into the stomach (in which case the patient will also spit up or vomit blood). In rare cases, where blood loss is especially heavy, the patient may feel light-headed, dizzy and may even faint.

Episodes of nose bleeding are self-evident. Where they are especially severe or recur, it is necessary to see a doctor. Lab tests will allow the doctor to evaluate underlying medical conditions that may be causing the severe bleeding.

Most nosebleeds can be self-treated by directly applying manual pressure to the nostrils, squeezing them between the fingers for 5 to 30 minutes. The head should be elevated, but not pushed too far back (in order to avoid swallowing blood).

If the vessel that is causing the bleeding is one that is easily seen and accessed, the doctor can seal it with a procedure called cauterisation. If the bleeding does not respond to cauterisation, nasal packing is an option. This involves placing an intra-nasal device, such as gauze, a type of balloon or sponge, to apply constant pressure. Nasal saline sprays may be useful for bleeding caused by excessive dryness.

Where bleeding is severe and recurring, medications are available to control the pain and to treat conditions causing the bleeds, such as vitamin K deficiency and high blood pressure. Antibiotics may be necessary to prevent infection.

Where severe nosebleeds keep occurring, surgery may be an option, such as arterial ligation. In this procedure, a doctor will tie up the specific blood veins causing the nosebleeds, preventing them from bleeding. This may require local or general anaesthesia.

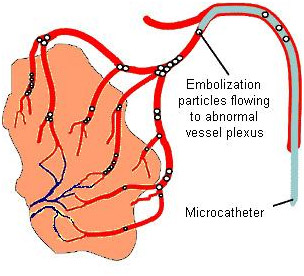

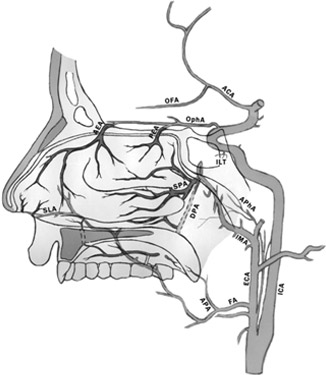

Some patients may not qualify for surgery, or surgery may not work. For those patients, embolisation, a minimally invasive procedure that requires local anaesthesia only, may be an alternative. This involves making a small cut, inserting a catheter into a peripheral artery, and using image guidance to move it to the vessels that lead to the point of the bleeding. The specialist will then use one of several materials, such as liquid tissue glue, microcoils, beads or particles, to block the bleeding vessel.

The specialist will also perform an angiography (using contrast material and X-ray to see how the blood is flowing through the arteries) both before and after the procedure.

It is a minimally invasive technique performed by an interventional radiologist. The interventional radiologist inserts a catheter into the patient’s femoral vein (in the upper thigh) using fluoroscopy for guidance. The interventional radiologist then directs the catheter to the affected arteriesresponsible for Epistaxis or nosebleed and inserts embolisation materials into the distal braches of arteries responsible for the bleeding to block the area, stopping the bleeding. The patient will have an angiography after the embolisation procedure to confirm if the procedure has been successful. The treatment has high rates of immediate clinical success.

You will already have undergone some tests including a computed tomography (CT) scan to identify the area of bleeding. You may also have had a endoscopy. You will be an inpatient for the procedure. You may be asked not to eat for four hours before the procedure. If you have any allergies or have previously had a reaction to the dye (contrast agent), you must tell the radiology staff before you have the test.a

A specially trained team led by an interventional radiologist within the radiology department. Interventional radiologists have special expertise in reading the images and using imaging to guide catheters and wires to aid diagnosis and treatment.

In the angiography suite or theatre; this is usually located within the radiology department. This is similar to an operating theatre into which specialised X-ray equipment has been installed.

You will be asked to get undressed and put on a hospital gown. A small cannula (thin tube) will be placed into a vein in your arm. The procedure will take place in the X-ray department and you will be asked to lie flat on your back. You may have monitoring devices attached to your chest and finger and may be given oxygen. Your groin area will be swabbed with antiseptic and you will be covered with sterile drapes. Local anaesthetic will be injected into the skin in your groin and a needle will be inserted into the artery. A fine plastic tube called a catheter will be placed into the artery. The radiologist uses X-ray equipment to guide the catheter towards the arteries that are responsible for Epistaxis or nosebleed. A special X-ray dye (contrast agent) is injected into the catheter to ensure a safe position for embolisation. The interventional radiologist can then block the abnormal arteries by carefully injecting tiny particles through the catheter guided by images on a screen. Small amounts of contrast are injected down the catheter to check that the abnormal arteries are blocked satisfactorily. Once the interventional radiologist is satisfied with the images, the catheter will be removed. Firm pressure will be applied to the skin entry point, for about ten minutes, to prevent any bleeding. Sometimes a special device may be used to close the hole in the artery.

Every patient is different, and it is not always easy to predict; however, expect to be in the radiology department for about two hours.

You will be taken back to your ward. Nursing staff will carry out routine observations including pulse and blood pressure and will also check the treatment site. You will stay in bed for at least six hours. You will be kept in hospital overnight and may be discharged the next day.