Haemoptysis refers to coughing up blood from the vessels in your respiratory tract below your voice box. Massive haemoptysis accounts for approximately 5% of cases of haemoptysis and is a life-threatening condition because it can result in asphyxiation (lack of oxygen). Because of the severity of the consequences, patients with haemoptysis need to be examined and treated as soon as possible.

Massive haemoptysis refers to when a patient coughs up between 100-1,000 ml of blood in 24 hours, but smaller amounts of blood can also be life-threatening, and so require interventional management.

In 90% of cases, the source of the bleeding is in the bronchi, the airways of the respiratory tract which conduct air into the lungs. In 5% of cases, the source of the bleeding is in the pulmonary system, which is the system that carries de-oxygenated blood away from the heart to the lungs and returns oxygenated blood back to the heart. There are a number of causes for haemoptysis, including tuberculosis, bronchitis and trauma.

The first step for evaluating haemoptysis is a chest radiograph, although the findings appear normal in up to 30% of cases. Another useful diagnostic approach is a bronchoscopy, in which an imaging device is inserted into the airway. CT may be used to find the source of the bleeding and to identify the cause.

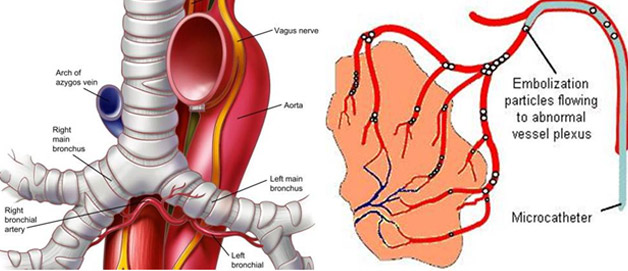

The treatment of choice for massive haemoptysis is bronchial artery embolisation, a minimally invasive technique performed by an interventional radiologist. The interventional radiologist inserts a catheter into the patient’s femoral vein (in the upper thigh) using fluoroscopy for guidance. The interventional radiologist then directs the catheter to the bronchial artery and inserts embolisation materials into the branch of the bronchial artery responsible for the bleeding to block the area, stopping the bleeding. The patient will have an angiography after the embolisation procedure to confirm if the procedure has been successful.

The treatment has high rates of immediate clinical success. If the bleeding recurs, the embolisation procedure can be repeated. There are a number of possible complications, including chest pain and difficulty swallowing. The most serious complication is inflammation of the spinal cord, but this only occurs in 1.4-6.5% of cases.

There are surgical treatments available, but these are reserved for cases where the embolisation procedure is unsuccessful or if the condition recurs after multiple embolisation procedures. Surgery has a mortality rate of 14-18%.

Other treatments include endobronchialtamponade, which is the use of an absorbent plug to stop the bleeding, and is used in patients who are not suitable candidates for embolisation or surgery. Another option is rigid bronchoscopy, which may be used to treat patients whose blood flow is impaired or who have breathing problems. Bronchoscopy can be used to clear the airways and aid physicians to carry out treatments.

The treatment of choice for massive haemoptysis is bronchial artery embolisation, a minimally invasive technique performed by an interventional radiologist. The interventional radiologist inserts a catheter into the patient’s femoral vein (in the upper thigh) using fluoroscopy for guidance. The interventional radiologist then directs the catheter to the bronchial artery and inserts embolisation materials into the branch of the bronchial artery responsible for the bleeding to block the area, stopping the bleeding. The patient will have an angiography after the embolisation procedure to confirm if the procedure has been successful.

The treatment has high rates of immediate clinical success. If the bleeding recurs, the embolisation procedure can be repeated. There are a number of possible complications, including chest pain and difficulty swallowing. The most serious complication is inflammation of the spinal cord, but this only occurs in 1.4-6.5% of cases.

You will already have undergone some tests including a chest X-ray and probably also a computed tomography (CT) scan to identify the area of bleeding. You may also have had a bronchoscopy. You will be an inpatient for the procedure. You may be asked not to eat for four hours before the procedure, although you may still drink clear fluids such as water. If you have any allergies or have previously had a reaction to the dye (contrast agent), you must tell the radiology staff before you have the test.

A specially trained team led by an interventional radiologist within the radiology department. Interventional radiologists have special expertise in reading the images and using imaging to guide catheters and wires to aid diagnosis and treatment.

In the angiography suite or theatre; this is usually located within the radiology department. This is similar to an operating theatre into which specialised X-ray equipment has been installed.

You will be asked to get undressed and put on a hospital gown. A small cannula (thin tube) will be placed into a vein in your arm. The procedure will take place in the X-ray department and you will be asked to lie flat on your back. You may have monitoring devices attached to your chest and finger and may be given oxygen. Your groin area will be swabbed with antiseptic and you will be covered with sterile drapes. Local anaesthetic will be injected into the skin in your groin and a needle will be inserted into the artery. A fine plastic tube called a catheter will be placed into the artery. The radiologist uses X-ray equipment to guide the catheter towards the arteries that are bleeding in your chest. A special X-ray dye (contrast agent) is injected into the catheter to ensure a safe position for embolisation. The interventional radiologist can then block the abnormal arteries by carefully injecting tiny particles through the catheter guided by images on a screen. Small amounts of contrast are injected down the catheter to check that the abnormal arteries are blocked satisfactorily. Once the interventional radiologist is satisfied with the images, the catheter will be removed. Firm pressure will be applied to the skin entry point, for about ten minutes, to prevent any bleeding. Sometimes a special device may be used to close the hole in the artery.

Every patient is different, and it is not always easy to predict; however, expect to be in the radiology department for about two hours.

You will be taken back to your ward. Nursing staff will carry out routine observations including pulse and blood pressure and will also check the treatment site. You will stay in bed for at least six hours. You will be kept in hospital overnight and may be discharged the next day.